Let's Make a Deal is a television game show which originated in the United States in the 1960s and has since been produced in many countries throughout the world. The program was created and produced by Stefan Hatos and Monty Hall, the latter of whom served as its emcee for many years.

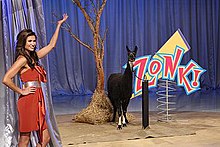

The format of Let's Make a Dealinvolves members of the studio audience, referred to as "traders", making deals with the host of the show. In most cases, a trader will be offered something of value and given a choice of whether to keep it or exchange it for another item. The program's defining game mechanic is that the other item is hidden from the trader until that choice is made. As such, the trader does not know if he/she is getting another item of value or what is referred to as a "Zonk", which is an item purposely chosen to be of little or no value to the trader.

Let's Make a Deal is also known for the various unusual and crazy costumes worn by audience members, who dressed up that way in order to increase their chances of being selected as a trader.[1]

The current edition of the show debuted in October 2009 on CBS with Wayne Brady as host, Jonathan Mangum as his announcer/assistant, and Alison Fiori as the show's prize model. Tiffany Coynejoined the series as Fiori's replacement in 2010 and musician Cat Gray joined the program in 2011. Danielle Demskifilled-in for Coyne while Coyne was on maternity leave for part of the 2013–14 season.

Broadcast history

Let's Make a Deal first aired on NBC in 1963 as part of its daytime schedule. The show moved to ABC in 1968 and remained there until 1976, and on two separate occasions the show was given a weekly nighttime airing on those networks.[2] The first syndicated edition of Let's Make a Deal premiered in 1971. Distributed by ABC Films, and then by its successor Worldvision Enterprisesonce the fin-syn rules were enacted, the series ran until 1977 and aired weekly.

A revival of the series based in Hall's native Canada was launched in 1980 and aired in syndication on American and Canadian stations for one season. This series was produced by Catalena Productions and distributed in America by Rhodes Productions, Catalena's partner company. In the fall of 1984, the series returned for a third run in syndication as The All-New Let's Make a Deal. Running for two seasons, ending in 1986, this series was distributed by Telepictures.

NBC revived Let's Make a Deal twice in a thirteen-year span. The first was a daytime series in 1990 that was the first to not be produced by Monty Hall. Instead, the show was a production of Ron Greenberg and Dick Clark. A primetime edition was launched in 2003 but drew poor ratings and was cancelled after three of its intended five episodes had aired.

A partial remake called Big Deal, hosted by Mark DeCarlo, was broadcast on Fox in 1996. In 1998 and 1999, Buena Vista Television (now Disney–ABC Domestic Television) was in talks to create a revival hosted by Gordon Elliott, but it was never picked up.[3] The show was one of several used as part of the summer series Gameshow Marathon on CBS in 2006, hosted by Ricki Lake.

As noted above, CBS revived Let's Make a Deal in 2009. The revival premiered on October 5, 2009, and CBS airs the show daily at 3:00 pm Eastern. Like the program that it replaced, the long-running soap opera Guiding Light, affiliates of the network are not locked in to airing the show at 3:00 pm and can air it whenever they wish. Some affiliates choose to continue a practice they started in the 1990s with Guiding Light and air Let's Make a Deal at 10:00 am Eastern, so that the show can serve as a lead in to The Price Is Right.

Beginning on September 20, 2010, Let's Make a Deal and The Price Is Right aired two episodes a day on alternating weeks. CBS did this to fill a gap between the final episode of As the World Turns, which ended a fifty-four year run on September 17, 2010, and the debut of The Talk, which was not scheduled to premiere until October 18, 2010. The double-run games aired at 2:00 pm Eastern.

Although the current version of the show debuted in September 2009, long after The Price is Right and the two Sony Pictures Television daytime dramas had made the switch to high definition, Let's Make a Deal was, along with Big Brother, one of only two programs across the five major networks that was still being actively produced in standard definition. For the start of production for its 2014–15 season in June 2014, Let's Make a Dealbegan being produced in high definition, with Big Brother 16 making the switch later in June. Let's Make a Deal was the last remaining CBS program to make the switch by air date, with the first HD episode airing on September 22, 2014.[4]

Past personnel

As noted above, Monty Hall was the longtime host of his creation. He hosted the original daytime network series for its entire run, and also hosted the accompanying primetime and syndicated series. After The All New Let's Make a Deal went off the air in 1986, Hall's full-time involvement with the show came to an end. Longtime game show announcer Bob Hilton was the initial host of the 1990 daytime series, but the producers decided to replace him with Hall partway through the run. Access Hollywood host Billy Bush emceed the 2003 series, with Hall making a cameo appearance in one episode.

Each Let's Make a Deal announcer also served as a de facto assistant host, as many times the announcer would be called upon to carry props across the trading floor. The original announcer for the series was Wendell Niles, who was replaced by Jay Stewart in 1964. Stewart remained with Let's Make a Deal until the end of the syndicated series in 1977. The 1980 Canadian-produced syndicated series was announced by Chuck Chandler. When the show returned as The All New Let's Make a Deal in 1984, the announcer/assistant position was first filled by voice actor Brian Cummings. He was replaced by Dean Gossfollowing the first season. The 1990 NBC revival series was announced by Dean Miuccio, with the 2003 edition featuring Vance DeGeneres in that role.

The longest tenured prize model on Let's Make a Deal was Carol Merrill, who stayed with the series from its debut until 1977. The models on the 1980s series were Maggie Brown, Julie Hall (1980), Karen LaPierre, and Melanie Vincz (1984). For the 1990 series, the show featured Georgia Satelle and identical twins Elaine and Diane Klimaszewski, who later gained fame as the Coors Light Twins.

Production locations

The original daytime series was recorded at NBC Studios in Burbank, California and then at ABC Television Center in Los Angeles once the program switched to the ABC network. The weekly syndicated series also emanated from ABC until the final season, when production moved to Las Vegas, Nevada and the ballroom of the Las Vegas Hilton.

The 1980 Canadian series taped at Panorama Studios in Vancouver, BC, which production company Catalena Productions used as its base of operations. Episodes of The All New Let's Make a Deal were taped at NBC Studios when the show premiered in 1984. After one season, the show moved to Hollywood Center Studios. The 1990 NBC daytime series was recorded at Disney-MGM Studios on the grounds of Walt Disney World in Orlando, Florida. The 2003 revival returned production to Burbank.

The current edition of the series originally was recorded in Las Vegas at the Tropicana Las Vegas, then moved to Sunset Bronson Studios in Hollywood, and is now taped at Raleigh Studios in Hollywood.

Format

Game play

Each episode of Let's Make a Dealconsists of several "deals" between the host and a member or members of the audience as traders. Audience members are picked at the host's whim as the show moves along, and couples are often selected to play together as traders. The deals are mini-games within the show that take several formats.

In the simplest format, a trader is given a prize of medium value (such as a television set or a few hundred dollars cash), and the host offers them the opportunity to trade for another prize. However, the offered prize is unknown. It might be concealed on the stage behind one of three curtains, or behind "boxes" onstage (large panels painted to look like boxes), within smaller boxes brought out to the audience, or occasionally in other formats. The initial prize given to the trader may also be concealed, such as in a box, wallet or purse, or the trader might be initially given a box, envelope or curtain. The format varies widely.

Technically, traders are supposed to bring something to trade in, but this rule has seldom been enforced. On several occasions, a trader is actually asked to trade in an item such as their shoes or purse, only to receive the item back at the end of the deal as a "prize". On at least one occasion, the purse was taken backstage and a high-valued prize was placed inside of it.

Prizes generally are either a legitimate prize, cash, or a Zonk. Legitimate prizes run the gamut of what is typically given away on game shows, including trips, electronics, furniture, appliances, and cars. Zonks are unwanted booby prizes(e.g., live animals, large amounts of food, fake money, fake trips or something outlandish such as a giant article of clothing, a room full of junked furniture, etc.). Sometimes Zonks are legitimate prizes but of a low value (e.g., Matchbox cars, wheelbarrows, T-shirts, grocery prizes, etc.). On rare occasions, a trader appears to get Zonked, but the Zonk is a cover-up for a legitimate prize.

Though usually considered joke prizes, traders legally win the Zonks.[5]However, after the taping of the show, any trader who had been Zonked is offered a consolation prize (currently $100) instead of having to take home the actual Zonk. This is partly because some of the Zonks are intrinsically or physically impossible to receive or deliver to the traders (such as live animals or the guy in an animal costume), or the props/employees are owned by the studio. A disclaimer at the end of the credits of later 1970s episodes read "Some traders accept reasonable duplicates of Zonk prizes." Starting in the 2012–13 season, CBS invited viewers to provide Zonk ideas to producers. At the end of the season, the Zonk declared the most creative was worth $2,500 to the winner, and other viewers' Zonk ideas were also used. For every viewer-developed Zonk, the host announced the viewer who provided the Zonk. The contest has been renewed for its second season in 2013.

Quickie Deals

As the end credits of the show roll, it is typical for the host to ask random members of the studio audience to participate in fast deals. In the current Wayne Brady version, these are often referred on the CBS version as "quickie deals", and are conducted by the host, announcer, and model each. CBS will post information on the show's Twitteraddress (@LetsMakeADeal) days before taping to encourage audience members to carry certain items in their pockets in order to win additional cash when one of the hosts approaches them at the end of the show and asks to see such items.[6] The deals are usually in the form of the following:

- Offering cash to one person in the audience who had a certain item on them.

- Offering a small cash amount for each item of a certain quantity.

- Offering cash for each instance of a particular digit as it occurred in the serial number on a dollar bill, driver's license, etc.

- Offering to pay the last check in the person's checkbook, if they had one, up to a certain limit (usually $500 or $1,000).

Other deal formats

Deals were often more complicated than the basic format described above. Additionally, some deals took the form of games of chance, and others in the form of pricing games.

Trading deals

- Choosing an envelope, purse, wallet, etc., which conceal dollar bills. One of them conceals a pre-announced value (usually $1 or $5), which awards a car or trip. The other envelopes contain a larger amount of money as a consolation prize. The trader must decide whether to keep their choice or trade. In some playings it is possible for more than one trader to win the grand prize.

- Making decisions for another person, such as a spouse or a series of unrelated traders. Sometimes after several offers, the teams are broken up to make an individual decision.

- Being presented with a large grocery item (e.g., a box of candy bars)—almost always containing a hidden cash amount—or a "claim check" at the start of the show. Throughout the show, the trader is given several chances to trade the item and/or give it to another trader in exchange for a different box or curtain. The final trader in possession of the item prior to the Big Deal is usually offered first choice of the three doors in exchange for giving up the item. The contents of the item are only revealed after the Big Deal is awarded (or prior to the Big Deal if the last trader with the item elected to choose one of the three doors).

- A variation of the above: A "cash box", with at various points the host inserting packets of money inside, with the trader allowed to give it to another trader in exchange for a curtain or box. As with the above deal, the host revealed the contents only after the last trader with the box goes for the Big Deal (again, he/she is given first choice of the doors) or after the Big Deal segment and before the closing credits.

Games of chance

A wide variety of chance-based games have been used on the show. Examples:

- Collecting a certain amount of money hidden inside wallets, envelopes, etc., or by pressing unlabeled buttons on a cash register, in order to reach a pre-stated "selling price" for a larger prize, such as a car, trip or larger amount of cash. Typically, there may also be one or more Zonk items hidden which end the game immediately if found. In the cash register game, if the Zonk button—the one that rings up "No Sale" – is found, the trader was offered a chance to find the second "No Sale" sign to win the grand prize, otherwise the trader won whatever amount was rang up, often double the amount. In the current CBS version, a board with thirteen cash amounts and two Zonks is used.

- Choosing one from among several items (e.g., one of three keys that unlocks a safe, one of three diamond rings that is genuine, one of three eggs that is raw, etc.) in order to win money or a prize. Sometimes, two or perhaps all three of the items would pay off with the stated prize, especially if multiple traders played.

- Games involving a deck of cards in which a trader must find matching cards, draw cards that reach a cumulative total within a certain number of draws, etc. to win a prize or additional money.

- Receiving clues about an unknown prize (such as a partial spelling of the prize or clues in the form or rap, rhyme, etc.) and deciding whether to take the unknown prize or a cash prize.

- Receiving money in the form of a long strip of bills dispensed one at a time from a machine. The trader can end the game at any time and keep the accumulated money, but he/she forfeits it if a blank sheet appears. Updated versions of the game involve an ATM. Depositing a card withdraws cash, but if the ATM displays "overdrawn" on the screen the trader loses everything.

- Rolling dice to receive cash based upon the roll or achieving a cumulative score within a certain number of rolls to win a larger prize.

Depending on the game, the trader is given the opportunity to stop the game at various points and take a "sure thing" deal or cash/prizes already accumulated or continue on and risk possibly losing.

Beat the Dealer

"Beat the Dealer" is a game played with three traders. The three traders choose a card from a board of nine cards (or after the show changed to high-definition, a board with nine "chips") to begin the game. The trader selecting the lowest number is eliminated (and wins $100), while the other two receive $500. In the second round, a prize package is shown to the traders. The two advancing traders select two more cards. The same elimination rules apply, with the trader having the higher number winning the prize package in addition to advancing to the final round. The remaining trader can quit with their winnings so far or risk them in an attempt to add a car. If the trader chooses to play, he or she selects a chip for himself or herself, and one for the host. Before the draw, the trader is given the option to keep the card first selected or pass it to the host. If the trader again chooses the higher number, he or she wins all the prizes announced, but choosing the lower number forfeits all prizes won to that point.

Prior to 2011, the three traders each choose an envelope which contained cash (two each of $500 or $1,000, depending on the version; with the third containing $50 or $100). The trader who found the smaller amount was eliminated, while the other two advanced to the second round.

Pricing games

Other deals related to pricing merchandise are featured in order to win a larger prize or cash amounts. Sometimes traders are required to price individual items (either grocery products or smaller prizes generally valued less than $100) within a certain range to win successively larger prizes or a car. Other times traders must choose an item that a pre-announced price or two items with prices that total a certain amount to win a larger prize. These games are not used on the CBS version because of their similarities to The Price is Right.

Quiz games

On the CBS version, in order to prevent similarities to The Price is Right, quiz games are used instead of pricing games. These deals involve products in the form of when they were introduced to the market, general knowledge quizzes, currency exchange rates (at the time of taping), or knowledge of geography of trips to certain locales used as prizes.

Door #4/Go for a Spin

Played every few days on the 1984–86 version, a trader was chosen at random by a computer based on a number (from 1 to 36) which appeared on the trader's name tag. The rules were revised several times early on, with the rules most associated with the game going into effect by later in the fall of 1984.

Those most common rules saw Hall give the trader a check for $1,000 and then offer him or her an opportunity to spin a carnival wheel containing money amounts ranging from $100 to $4,000, plus several spaces marked "Zonk". Two other spaces on the wheel were marked with the word "car". The trader could either keep the $1,000 or exchange it to spin the wheel. If the trader chose to spin the wheel, the trader was awarded the prize associated with the space on which the wheel stopped. If the wheel stopped on a Zonk space, he or she received a T-shirt saying "I was ZONKED by Monty Hall". Even if the trader decided to keep the initial $1,000, he or she was asked to spin the wheel to see how the game would have ended.

The first few times Door #4 was featured, the trader was offered a sure-thing prize package or going for Door #4, which hid a cash amount of anywhere from $1 to $5,000. When the carnival wheel was initially introduced, the wheel contained cash amounts from $100 to $5,000. The trader spun the wheel and could keep the cash amount on which the wheel stopped, or risk their winnings for another spin. However, if the amount of the second spin was less than the first amount spun, the trader won nothing. Also on the wheel was a space marked "Double Deal", which doubled the trader's spin, for a possible total of $10,000. If the trader spun Double Deal with both spins, he or she also won $10,000. When the permanent rules were first introduced, the initial cash prize was $750, with the wheel's top cash prize at $3,000.

A revamped version, titled "Go for a Spin", was first played on the December 20, 2011 episode.[7] A trader is selected and shown a sixteen-space wheel, with various cash amounts, five Zonk spaces and one car space. The trader is then asked three questions with two choices each, and attempts to choose the option preferred by the audience in an earlier poll. For each correct choice selected, the trader wins $500 and one Zonk space of the trader's choice is converted to a car space. The trader can keep the money earned or trade it in for one spin of the wheel. If the trader chooses to spin, the trader wins whatever is indicated in the space on which the wheel stops.

Big Deal

The Big Deal serves as the final segment of the show and offers a chance at a significantly larger prize for a lucky trader. Before the round, the value of the day's Big Deal is announced to the audience.

The process for choosing traders was the same for every series through the 2003 NBC primetime series. Monty Hall (or his successors) would begin asking the day's traders, usually starting with the highest winner, if they wanted to give back what they had managed to win earlier in the show for a chance to choose one of three numbered doors on the stage. The process continued until two traders agreed to play, and the biggest winner of the two got first choice of Door #1, Door #2, or Door #3. The other trader then chose from the remaining two doors. Since the 2009 series, the Big Deal has been played with just one trader.

Each of the doors conceals a prize package of some sort. Other times, a door could conceal an all cash prize hidden inside "Monty's Piggy Bank" or "Monty's Cookie Jar", or even behind a "Let's Make a Deal Claim Check" or some other prop. The doors are opened in ascending order, with the Big Deal always revealed last no matter if it was selected or not. The Big Deal prize was usually the most extravagant of the night, and was often a car or a vacation with first-class accommodations. On rare occasions, the Big Deal involves one of the all cash prize props mentioned above; in most cases, such as when a car is not part of the package, a cash prize is awarded as part of the Big Deal.

The Big Deal is the one time in the show where a trader is guaranteed to not walk away with a Zonk. However, it is possible for traders to trade their prizes from earlier in the show and have the prize package behind their chosen door be worth somewhat less than the original prize was.

Super Deal

During the 1975–76 syndicated season, winners of the Big Deal were offered a chance to win the "Super Deal". At this point, Big Deals were limited to a range of $8,000 to $10,000. The trader could risk their Big Deal winnings on a shot at adding a $20,000 cash prize, which hidden behind only one of three mini doors onstage. The other two doors contained cash amounts of $1,000 or $2,000; however, the $1,000 value was later replaced with a "mystery" amount between $1,000 and $9,000. A trader who decided to play risked their Big Deal winnings and selected one of the mini doors. If the $20,000 prize was behind the door, the trader kept the Big Deal and added the $20,000 prize, for a potential maximum total of $30,000. However, if a trader selected one of the other two doors, he or she forfeited the Big Deal prizes but kept the cash amount behind the door. The Super Deal was discontinued when the show permanently moved to Las Vegas for the final season (1976–77), and Big Deal values returned to the previous range of $10,000 to $15,000.

Since 2012, the Super Deal is offered as a limited event and is not played regularly. The show will designate one or two weeks of episodes, typically airing during a special event (e.g., the 500th episode, 50th anniversary of franchise, etc.), each season for the Super Deal. If a trader wins the Big Deal, he or she can risk their Big Deal winnings for the same 1-in-3 chance at a cash prize of $50,000. Rather than choosing mini doors, the trader selects one of three envelopes labelled ruby, emerald, and sapphire. Similar to the 1975 format, the trader keeps the Big Deal in addition to the cash prize if he or she selects the envelope containing $50,000.

Reception

Upon the original Let's Make a Deal's debut, journalist Charles Witbeck was skeptical of the show's chances of success, noting that the previous four NBC programs to compete with CBS' Password had failed.[8] Some critics described the show as "mindless" and "demeaning to traders and audiences alike".[9]

By 1974, however, the show had spent more than a decade at or near the top of daytime ratings, and became the highest-rated syndicated primetime program.[9] At the time, the show held the world's record for the longest waiting list for tickets in show-business history[9][10] – there were 350 seats available for each show, and a wait time of two-to-three years after requesting a ticket.[9][10]

In 2001, Let's Make a Deal was ranked as #18 on TV Guide's list of "The 50 Greatest Game Shows of All Time".[11]In 2006, GSN aired a series of specials counting down its own list of the "50 Greatest Game Shows of All Time", on which Let's Make a Deal was #7.[12]

In 2014, the American series won a Daytime Creative Arts Emmy Award for Outstanding Original Song for "30,000 Reasons to Love Me", composed by Cat Gray and sung by Wayne Brady.[13]

Episode status

Many of the show's estimated five thousand plus episodes exist:

- NBC Daytime/Nighttime: Status is unknown, though it is very likely that the original tapes were wiped as they were recorded over by NBC with new programming in an era when videotape was prohibitively expensive. The 1963 pilot exists, with Wendell Niles as announcer, traders in normal business attire (typical of its first season), and a Zonk behind one of the doors in the Big Deal (worth $2,005). Zonks have never officially been in the big deal. The 1967 nighttime finale exists in the Library of Congress,[citation needed] along with a few scattered daytime episodes. Three daytime episodes are at the Paley Center for Media.[citation needed]

- ABC Daytime: More than 500 episodes exist.[citation needed] A clip from the ABC daytime premiere was used on Monty Hall's "Biography", which aired during Game Show Week on A&E. Another episode from 1969 was found,[citation needed] which features a gaffe that Hall himself rated as his most embarrassing moment on Let's Make a Deal – at the end of the show, he attempted to make a deal with a woman carrying a baby's bottle. Noting that it had a removable rubber nipple, he offered the woman $100 if she could show him another nipple. This clip was restored utilizing the LiveFeed Video Imaging kinescope restoration process, and was re-aired in 2008 as part of NBC's Most Outrageous Momentsseries. Episodes substitute-hosted by Dennis James exist in his personal library.[14]

- ABC Nighttime/1971–77 Syndicated: Exist almost in their entirety[citation needed]and have been seen on GSN in the past. The CBN Cable Network reran the syndicated series in the 1980s and its successor, The Family Channel, from June 7, 1993[15] to March 29, 1996.[16]Episodes of this version currently airs on Buzzr.

- The 1980–81 Canadian version was seen in reruns on the Global Television Network for much of the 1980s.[citation needed]

- The 1984–86 syndicated version has been seen on GSN in the past. Reruns previously aired on the USA Networkfrom December 29, 1986[17] to December 30, 1988[18] and The Family Channel from August 30, 1993[19] to March 29, 1996.[20]

- The 1990s NBC version has not been seen since its cancellation.

- The 2003 NBC prime time version only aired three of the five episodes produced, with no rebroadcasts since.

International versions

Merchandise

In 1964, Milton Bradley released a home version of Let's Make a Deal featuring gameplay somewhat different from the television show. In 1974, Ideal Toysreleased an updated version of the game featuring Hall on the box cover, which was also given to all traders on the syndicated version in the 1974–75 season. An electronic tabletop version by Tiger Electronics was released in 1998. In the late summer of 2006, an interactive DVD version of Let's Make a Deal was released by Imagination Games, which also features classic clips from the Monty Hall years of the show. In 2010, Pressman Toy Corporation released an updated version of the box game, with gameplay more similar to the 1974 version, featuring Brady on the box cover.[21]

Various U.S. lotteries have included instant lottery tickets based on Let's Make a Deal.[22]

In 1999, Shuffle Master teamed up with Bally's to do a video slot machine game based on the show with the voice and likeness of Monty Hall.

In 2004, IGT (International Gaming Technology) did a new video slot game based on the show still featuring Monty Hall.

In 2013, Aristocrat Technology did an all-new video slot machine game based on the Wayne Brady version.

The Monty Hall Problem

The Monty Hall Problem, also called the Monty Hall paradox, is a veridical paradox because the result appears impossible but is demonstrably true. The Monty Hall problem, in its usual interpretation, is mathematically equivalent to the earlier Three Prisoners problem, and both bear some similarity to the much older Bertrand's box paradox. The problem examines the counterintuitive effect of switching one's choice of doors, one of which hides a "prize".

The problem has been analyzed many times, in books, articles and online.[23][24] In an interview with The New York Times reporter John Tierneyin 1991, Hall gave an explanation of the solution to that problem, stating that he played on the psychology of the trader, and why the solution did not apply to the case of the actual show.

No comments:

Post a Comment